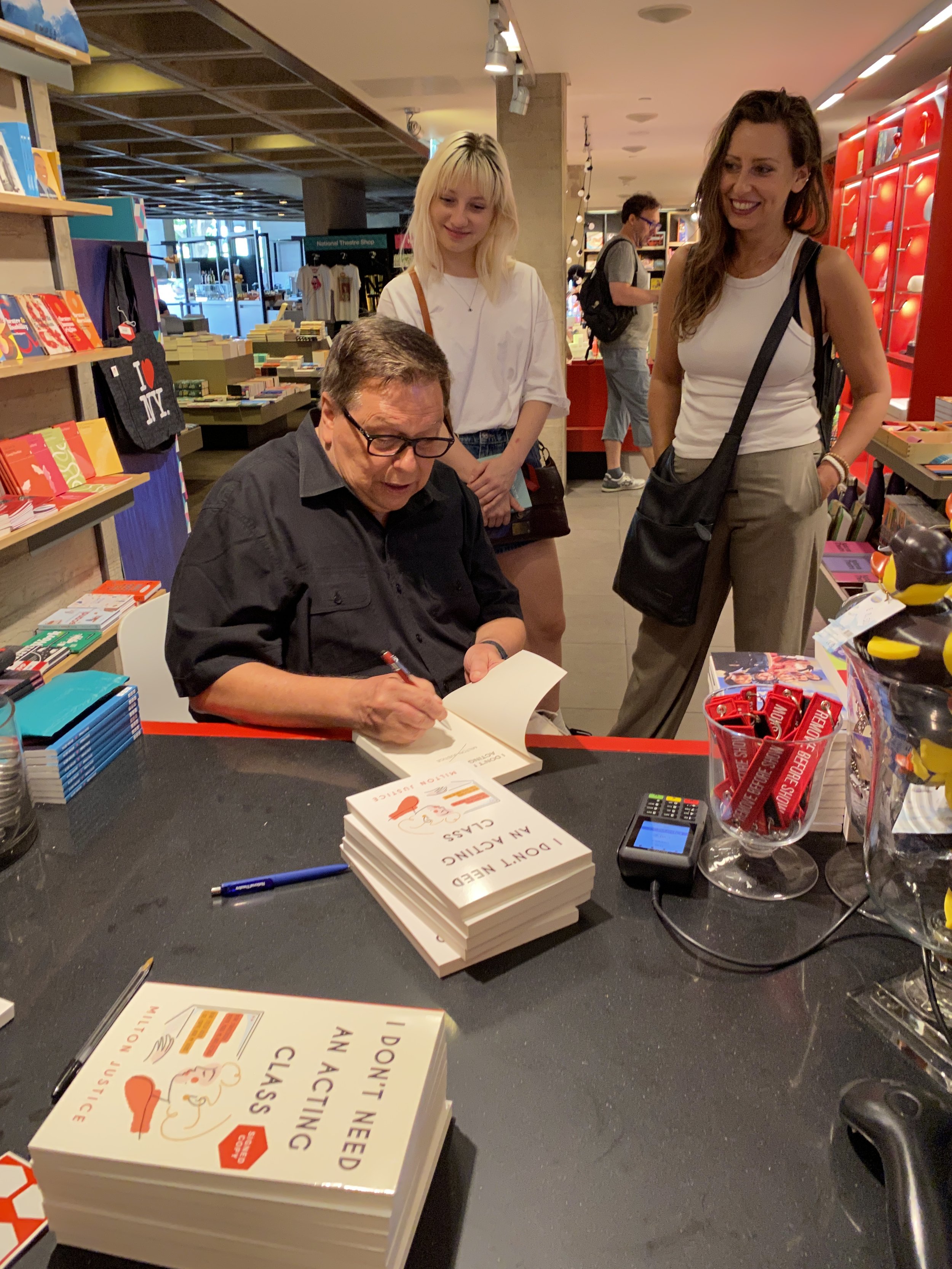

The Teacher As Actor Part 5: Guest blog by Milton Justice

Make sure to check out Episode 71 The Teacher As Actor Part Two with Milton Justice.

Acting and Teaching

When I first started teaching I asked Jack Heifner, whose play Vanities I’d produced off Broadway, what it was like to teach. He’d been teaching for a year and I figured, since he was a playwright and new to it, he’d be a good source for an opinion. “It’s like stand-up comedy. If the material isn’t working, you switch to something else.” I thought he was kidding, but he was dead on. Nothing is clearer than when the class is bored. The challenge is non-stop.

As I think of the idea of acting and teaching as a concept, I figure I should start with several ideas about acting that I think apply. As a note of importance: Not only do I think it’s impossible to simplify acting into a quick phrase, I think it undermines the challenging difficulty of what is truly a lifelong search. All sorts of acting teachers have made the mistake of trying to do that. Even famous ones. Uta Hagen led us to believe that “Acting is reacting.” And Sandy Meisner thought he was helping by saying, “Acting is living truthfully in imaginary circumstances.” Neither helps the actor and it certainly doesn’t help the teacher.

For the purpose of this blog, I think it’s most useful for me to start with the Russian word: zadacha. Stanislavski, the mother-father-God of acting, used this word to describe what was true about every character. The translation from the Russian is “problem.” What Mr. Stanislavski was saying was that every character has a problem. And, clearly, if you have a problem, you want to solve it. [By the way, it was mis-translated into English as “objective” by the original translator, Elizabeth Hapgood. Of interest is that Ms. Hapgood was a Russian scholar, not an actress.]

Both as actors and as teachers we need to dig into the depth of the ideas. Most actors don’t. And that’s why so many actors are ineffective. They memorize the lines and try to say them intelligently. I fear many teachers are the same way. In essence they’re memorizing the lines and reporting them.

So what exactly are we trying to do?

Every fact of every play is dead until it’s fed through the imagination of the actor and becomes the experience of the facts. It doesn’t matter how brilliant the analysis of Death of a Salesman or Long Day’s Journey Into Night might be, until it’s brought to life through the soul of the actor, it’s like a lifeless essay. Trust me, nothing is more boring than hearing a group of actors talking about the meaning of a play. One always wonders why we didn’t see all of that interesting discussion translated to the performances on stage. In fact it is exactly the reason we don’t hand out the script to the audience, so they can read it and go home. It’s not about the words on the page, it’s about the characters that are brought to life on the stage.

I had an experience recently directing a production of The Glass Menagerie. I cast a woman in the role of Amanda who was not a professional actress, but rather a teacher (and a mother). A brilliant teacher, who has taught English at the North Carolina School of the Arts for the past twenty years. I cast her because I knew she would bring a humanity to a part that often feels like it’s an actress playing a Southern mother. Beth was wonderful in the part. She commented at one point on the difference between approaching the play as literature and approaching it as an actress: You can’t just analyze and admire the structure; the characters don’t know they’re a theme and they certainly don’t know that they’re living in a structure. What is important is that we understand what Amanda is experiencing.

The most important word in acting is experiencing. I would extend that to teaching. Students respond to how we experience what we teach them. If we couple this idea with zadacha – the problem, we get a clear picture of how acting applies to teaching.

If I use my own teaching as an example, when I teach Script Analysis, I am aware that the problem with my students is they approach great plays in a pedestrian manner. They have no sense that these great plays are great because the ideas are cosmic! What I try to do to solve this problem is to get them to see how monumentally important the themes are. In a sense what I’m doing is lifting them up to the size of the ideas. There is obviously no way that I can do this by simply “reporting” what I’ve read. Without experiencing what I’m talking about, they might as well read it in a book. In fact, one of my biggest problems is having actors who’ve read too many acting books. [Keeping in mind, I’ve also written one.]

Acting is about bringing living, breathing human beings to life on the stage, people who are lifeless on the page, a collection of words and sentences. Teaching can be nothing more than a collection of words and sentences unless the teacher brings these words and sentences to life.